st, but these SHORT reminiscences have turned out to be a little longer than I figured. They tend to lengthen as I add the “extra” stuff, like story setup and details. You have to admit, without an adequate “setup,” the mind-boggling stuff just doesn’t seem to “boggle” like it should. As they say, both God AND the devil are in the details. In the Air Force we called it “fluff.” Well… I LIKE my fluff. So, let the fluff begin!

st, but these SHORT reminiscences have turned out to be a little longer than I figured. They tend to lengthen as I add the “extra” stuff, like story setup and details. You have to admit, without an adequate “setup,” the mind-boggling stuff just doesn’t seem to “boggle” like it should. As they say, both God AND the devil are in the details. In the Air Force we called it “fluff.” Well… I LIKE my fluff. So, let the fluff begin!Trash in the road:

From 1982 through 19

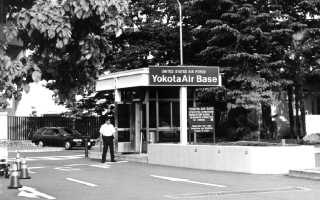

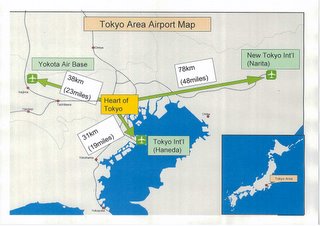

86, I lived and worked in Japan. Hardly a day went by that I didn’t bicycle or run on and around Yokota Air Base, my home for those four unforgettable years. From my travels on foot and bike, I knew every inch of road and trail for miles around the base. It was a splendid place to bicycle and run, and I totaled literally thousands of miles doing both. But whenever I ventured off base, to stay healthy—to keep bones unbroken, and skin unbloodied—I really had to stay on my toes, for danger lurked around every corner.

86, I lived and worked in Japan. Hardly a day went by that I didn’t bicycle or run on and around Yokota Air Base, my home for those four unforgettable years. From my travels on foot and bike, I knew every inch of road and trail for miles around the base. It was a splendid place to bicycle and run, and I totaled literally thousands of miles doing both. But whenever I ventured off base, to stay healthy—to keep bones unbroken, and skin unbloodied—I really had to stay on my toes, for danger lurked around every corner.The neighborhood streets w

ere the narrowest and busiest I’ve seen anywhere in the world—they wound-around, doubled-back, dead-ended and were nearly impossible for a non-local to navigate. Running through the narrow lanes, especially in Japanese residential areas, was like making my way through a rat’s maze, except that there were thousands of other “rats” in the maze with me; and all of them driving cars, bikes, and scooters, or, on foot, like me. Many of the corners were blind, so in the interest of self-preservation, I learned to make good use of the many circular mirrors set high up on poles, or on the sides of buildings. These ubiquitous mi

ere the narrowest and busiest I’ve seen anywhere in the world—they wound-around, doubled-back, dead-ended and were nearly impossible for a non-local to navigate. Running through the narrow lanes, especially in Japanese residential areas, was like making my way through a rat’s maze, except that there were thousands of other “rats” in the maze with me; and all of them driving cars, bikes, and scooters, or, on foot, like me. Many of the corners were blind, so in the interest of self-preservation, I learned to make good use of the many circular mirrors set high up on poles, or on the sides of buildings. These ubiquitous mi rrors allowed travelers to see what was coming from around each tight corner. Without them, traffic would have to slow to a crawl or run the constant risk of collision.

rrors allowed travelers to see what was coming from around each tight corner. Without them, traffic would have to slow to a crawl or run the constant risk of collision.The constricted streets—actually they were more like alleys than streets—twisted, turned, and doubled back so subtly, that I spent much of the time lost and confused. After awhile, it became an amusing game for me—to get lost, and then to work to regain my bearings. At times, I’d just go as straight as I could, until I ran into a major thoroughfare that I recognized, at which point I tried to follow it in the correct direction. If I got turned around, I had a 50-

50 chance of going the wrong way, and THAT could make for a very long day. The one place I NEVER got lost though, was up in the hills that ringed the base to the Southwest.

50 chance of going the wrong way, and THAT could make for a very long day. The one place I NEVER got lost though, was up in the hills that ringed the base to the Southwest.As a hill lover, my first inclination is to go to high ground anyway. For some reason, “Run for the Hills!” has always been my personal credo. As long

as I was in the hills overlooking Yokota, or near enough to see them, I could always figure out which way to go to find my way back home. Plus, I loved the challenge of running up steep inclines; nothing tests a runner or a biker more than a long, tough stretch of uphill going. On days when I really had no plan as to my route for that day, I usually turned left out the back gate, and headed toward my beloved hills.

as I was in the hills overlooking Yokota, or near enough to see them, I could always figure out which way to go to find my way back home. Plus, I loved the challenge of running up steep inclines; nothing tests a runner or a biker more than a long, tough stretch of uphill going. On days when I really had no plan as to my route for that day, I usually turned left out the back gate, and headed toward my beloved hills.One cool spring day, I found myself up in those lovely hills, enjoying an exceptionally long run

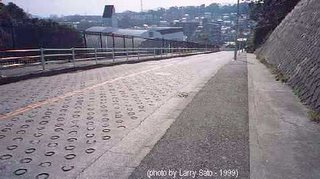

past tiny tea plantations, hillside temples, and cemeteries. I was so far out, that most of my route was over streets upon which I had never trod before. I had been running a busy, and for once wide, asphalt road that followed the ridge top for several miles, and after about an hour and half, I decided I’d better start making my way home before I ran out of steam. After another half-mile I came upon an intersection that looked promising, so I turned right hoping to head back downhill onto the Kanto Plain and home to Yokota Air Base.

past tiny tea plantations, hillside temples, and cemeteries. I was so far out, that most of my route was over streets upon which I had never trod before. I had been running a busy, and for once wide, asphalt road that followed the ridge top for several miles, and after about an hour and half, I decided I’d better start making my way home before I ran out of steam. After another half-mile I came upon an intersection that looked promising, so I turned right hoping to head back downhill onto the Kanto Plain and home to Yokota Air Base.That steep, two-lan

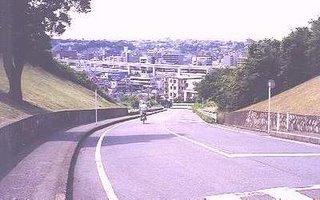

e street wound back-and-forth, and grew steeper as I ran down it. The narrow lane barely had a shoulder, and was just wide enough to accommodate two-way traffic. It twisted and turned so often that I rarely could see more than 50 feet ahead before it turned into another blind bend. People driving cars and peddling bicycles also seemed enthused by the smooth downhill twists and turns, and the lack of any real sidewalks or shoulder forced me to pay rapt attention, or chance getting nailed by these fellow downhill “racers.”

e street wound back-and-forth, and grew steeper as I ran down it. The narrow lane barely had a shoulder, and was just wide enough to accommodate two-way traffic. It twisted and turned so often that I rarely could see more than 50 feet ahead before it turned into another blind bend. People driving cars and peddling bicycles also seemed enthused by the smooth downhill twists and turns, and the lack of any real sidewalks or shoulder forced me to pay rapt attention, or chance getting nailed by these fellow downhill “racers.”Well past half way down, my second wind kicked in, and in spite of the length of time I’d already been running, my speed picked up. It felt like I was on wheels instead of pumping legs. Or perhaps floating is the better description, as if I had no body, only a quickly moving spirit. Only another runner who has been in tiptop shape can understand the feeling of running like an ethereal spirit.

I was just finishing negotiating a particularly tight S-turn, best described as a double bend, when as I came around the last sharp turn, I saw what appeared to be a mound of odd-looking blue trash laying in the center of my lane. Remember, the Japanese drive on the left side of the road. The blue rubbish pile was right in my line of travel, so I shortened my stride in preparation of jumping over it. But within just a couple of strides from taking my leap, I saw it wasn’t trash at all! My heart nearly jumped out of my throat, so shocked I was at what it ACTUALLY was.

Instead of jumping over it, I veered quickly to the right and came to a skidding stop. It wasn’t wayward rubbish at all; what I had actually come upon was an ancient little Japanese man in a blue tracksuit that had just wrecked his little blue bicycle—of a sort ridden by millions of

Japanese. At first glance, he didn’t look alive. His face was blanched a deathly white. A trickle of blood ran down his nose and cheek from a deep cut on his forehead. His arms and legs were tangled up with the thick frame of his blue bicycle, so much so, that I thought he’d broken all four of his limbs, and perhaps his back and neck as well. I noticed his left hand was badly scraped and also cut and bloody. It was an appalling, heartrending sight.

Japanese. At first glance, he didn’t look alive. His face was blanched a deathly white. A trickle of blood ran down his nose and cheek from a deep cut on his forehead. His arms and legs were tangled up with the thick frame of his blue bicycle, so much so, that I thought he’d broken all four of his limbs, and perhaps his back and neck as well. I noticed his left hand was badly scraped and also cut and bloody. It was an appalling, heartrending sight.I quickly realized he was still alive from his short shallow breathing. He

made strange gurgling animal-like noises occasionally, like he was in pain. About then, I became concerned that both us of were about to get clobbered by cars coming around the uphill bend, from the direction I had just come from. Bending over his twisted body I felt completely vulnerable as one car after another barely missed us. As a half-dozen cars passed by us with inches to spare, I spoke to the old guy trying to reassure him, “Hey buddy, don’t worry. You’re going to be okay. Just hang in there and I’ll get help.” I doubt if he understood me, and from the lack of movement from his half-closed eyes, I assumed he was unconscious, but he seemed to respond as he made another groaning noise.

made strange gurgling animal-like noises occasionally, like he was in pain. About then, I became concerned that both us of were about to get clobbered by cars coming around the uphill bend, from the direction I had just come from. Bending over his twisted body I felt completely vulnerable as one car after another barely missed us. As a half-dozen cars passed by us with inches to spare, I spoke to the old guy trying to reassure him, “Hey buddy, don’t worry. You’re going to be okay. Just hang in there and I’ll get help.” I doubt if he understood me, and from the lack of movement from his half-closed eyes, I assumed he was unconscious, but he seemed to respond as he made another groaning noise.Another car sped past, barely pausing, before continuing down the hill. Now I was getting angry. I could see these cowardly drivers look at me as they passed with absolutely no expression, and when I made an imploring gesture at them for help, they quickly turned away and kept going. I heard another car coming and I jumped to my feet in front of him with both hands held high—the universal sign language for STOP YOU S.O.B! A driver, a middle-aged man, in a white Toyota slowed down and tried to go around, but I shifted my body in front of him. “Stop! Damn you!” I yelled putting my hands on the hood of his car.

He stopped directly in front of us, giving the fallen old man and me some protection from getting squashed by the fast-moving cars. The driver got out of his Toyota sedan and spoke to me rapidly in Japanese; I didn’t understand a word, but I was able to ask him with the few Japanese phrases I knew at the time, “Where is a phone? Call for an ambulance. Please!” He answered me, again I didn’t understand, but I was encouraged to see him running to a building. The good thing is he left the car where it was, so it continued to protect us.

I took my shirt off and gently place it under the old guys head, hardly lifting it in case he had some kind of neck injury. Then I bent down close him so he could continue to hear me speak soothing words. I knew if I was in that predicament, that I’d want someone talking to me like everything was going to be okay. I looked up when I heard the white Toyota being started and then watched it drive past us. I was horror-stricken. The driver never even looked at me. ‘What the hell!’ I thought.

Once again, we were at the mercy of speedy traffic coming from around the bend. Sometimes the cars would mash their brakes and fishtail alarmingly before regaining momentum and speeding by, and others merely swerved expertly around us. I was fearful and enraged at their lack of compassion. An old model car, a rarity in Japan, coming from the downhill direction slowed and stopped; two old Japanese gentlemen, probably in their 60s, sat in the front. The driver asked me through the window in surprisingly clear American-accented English, “Has anyone called an ambulance?”

I answered, “I hope so!” Then I told him about the guy in the white Toyota, that he might have called, but I wasn’t sure. I was utterly gratified that I was no longer alone and solely responsible for the welfare of the distressed old gentleman lying so pitifully on the street. The old boys, undoubtedly MY saviors as well as the old man’s, got out of their parked car and hurried over. The first thing they decided to do was to lift both the injured man along with his bicycle, and move him out of the middle of the road. I was very concerned about doing that, and I did my best to support the unconscious fellow’s back and neck as much as possible, while they half lifted and half-dragged the bike and fallen rider out of the path of oncoming cars.

I scooped up my t-s

hirt, sweaty from me and spotted with blood from the old man, and I happily pulled it back on. It felt cold and clammy in the chilly air. I stood there, for a few minutes, and when I realized that I was no longer needed; I took off jogging again, back down the hill in my original direction. About then I heard the distinctive sound of a Japanese ambulance siren approaching from the bottom of the hill. At the same time, a young woman, probably the hurt gentlemen’s granddaughter or daughter, passed me hurrying up the hill, looking frightened and worried.

hirt, sweaty from me and spotted with blood from the old man, and I happily pulled it back on. It felt cold and clammy in the chilly air. I stood there, for a few minutes, and when I realized that I was no longer needed; I took off jogging again, back down the hill in my original direction. About then I heard the distinctive sound of a Japanese ambulance siren approaching from the bottom of the hill. At the same time, a young woman, probably the hurt gentlemen’s granddaughter or daughter, passed me hurrying up the hill, looking frightened and worried.I took a deep breath, sighed, and got my mind back into the task of finding my way back to base. I still had a good hour or more of running before I would be back in the comfort of my home in base housing. I looked down at the smudge of blood on my shirt; that spot was my link to reality, because what had just happened was so surreal that it was already feeling like a dream.

2 comments:

Hello Phil. Visting your blog from Ed Abbey's. It's sad but unfortunately in urban areas in the Philippines (like Manila) the same is true. There was once a man apparently attacked an he went to the building lobby asking for help. The people there just stood and stared. A couple of foreigners saw the man and helped him get to the hospital. I got word of this when we passed by and saw some people still lingering and informed us what happened. Sad.

Hi Watson. You could be right, that it's an urban thing, this disconnect of people from their fellow man. The Japanese are much worse about it than Filipinos. I took a spill on my scooter over a year ago and became trapped under it in the middle of the road. Five Filipinos immediately came to my aid and made sure I was okay.

In Japan I have come across accidents where not ONE local person would stop to help. My friend, a fellow airman, was in a Japanese McDonalds when a boy fell to the floor with a seizure. It was only two American GIs in there that came to the poor fellow's assistance, putting a belt in his mouth and holding his head to protect him while he bounced around on the deck. All the locals stood there and watched as if paralyzed.

Stories like these about Japanese unwillingness to come to the aid of others are numerous among Americans who have lived there.

For instance, my buddy, another American airman, was sitting in traffic on his motorcycle when he witnessed a motorcycle cop get hit full on by a semi-truck. The Japanese cop was thrown directly into the middle of the intersection causing all traffic to come to a complete stop. My friend sprang off his bike, threw off his helmet, and ran to the unconcious policeman. He had been split open from his chest to his cheek and he was literally drowning in his own blood as he lay on his back. My buddy saved his life by simply turning him on his side to allow the blood to drain away from his windpipe.

What disgusted my buddy was that not a single person left the security of their car to help. He stood up and looked around at all these people, sitting upright, eyes wide, grasping their steering wheels with both hands and staring straight ahead. He marvelled that if he hadn't happened to have been there, that man would have died as all those people looked on!

I would much rather be hurt and in need of help here than in Japan. You might not keep your wallet here, but you'll more than likely get help!

Post a Comment