+++++++A Technician's Story+++++++

By the time I got to Little Rock Air Force Base in Arkansas, I had been in the Air

Force for just six years. I had transferred over after doing 5 years with the Marines, where I had worked in aviation administration along with a tour in embassy security; so even though I had some rank, I wasn’t a very experienced technician when it came to my Air Force duties. And because of my relative lack of technical know-how, there were times in the USAF that I felt like a pretender.

Force for just six years. I had transferred over after doing 5 years with the Marines, where I had worked in aviation administration along with a tour in embassy security; so even though I had some rank, I wasn’t a very experienced technician when it came to my Air Force duties. And because of my relative lack of technical know-how, there were times in the USAF that I felt like a pretender.From Little Rock, USA to Mildenhall in the UK

Less than a year after arriving in Little Rock from a 4-year stint in Japan, I was sent TDY, the Air Force abbreviation for the term “temporary duty,” to Mildenhall Royal Air Base for 90 days. Even though I had only 6 years in the Air Force, as a technical sergeant, I was the highest-ranking fellow of the eight of us sent from the Instrument Autopilot Shop. My shopmates from Arkansas had much more experience on the C-130E than I did, but rank is rank, so I was in charge.

Less than a year after arriving in Little Rock from a 4-year stint in Japan, I was sent TDY, the Air Force abbreviation for the term “temporary duty,” to Mildenhall Royal Air Base for 90 days. Even though I had only 6 years in the Air Force, as a technical sergeant, I was the highest-ranking fellow of the eight of us sent from the Instrument Autopilot Shop. My shopmates from Arkansas had much more experience on the C-130E than I did, but rank is rank, so I was in charge.My responsibilities included scheduling my people

(as well as myself) to ensure 24-hour coverage for all nine of our “birds,” as they came and went from missions all over Europe, Western Asia, The Middle East, and Africa. On top of all that, I was expected to pull my weight troubleshooting and repairing “our” avionics systems. (We were responsible for instrument indicating systems, the compasses, and the autopilot). So, I was in charge, but I was also just another “snuffy” when it came to covering my 12-hour shift. It was a lot of responsibility, but it came with the rank, and it was why I earned the “big bucks!” as we used to say sarcastically.

(as well as myself) to ensure 24-hour coverage for all nine of our “birds,” as they came and went from missions all over Europe, Western Asia, The Middle East, and Africa. On top of all that, I was expected to pull my weight troubleshooting and repairing “our” avionics systems. (We were responsible for instrument indicating systems, the compasses, and the autopilot). So, I was in charge, but I was also just another “snuffy” when it came to covering my 12-hour shift. It was a lot of responsibility, but it came with the rank, and it was why I earned the “big bucks!” as we used to say sarcastically. "Goosed" in Goosebay

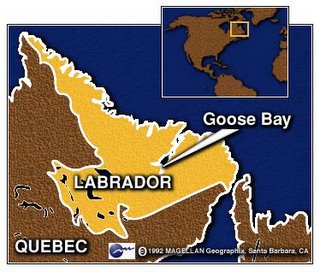

I made the interminable flight to England in one of our nine aircraft. During the journey, we stopped way up in northeastern Canada at a place called Goosebay Labrador. The aircraft came to a jerking stop, the crew door lowered into its alternate function as a stepway, and the lot of us, about 25 airmen of various ranks and fields, made our way stiffly off the airplane. A bitterly cold arctic night greeted us, the wind stinging our unprotected faces with specks of icy snow. One of my shopmates assigned to the ADVON team waited impatiently at the bottom of the ladder for us to clear off the aircraft so he could get to work. (ADVON stands for advanced

I made the interminable flight to England in one of our nine aircraft. During the journey, we stopped way up in northeastern Canada at a place called Goosebay Labrador. The aircraft came to a jerking stop, the crew door lowered into its alternate function as a stepway, and the lot of us, about 25 airmen of various ranks and fields, made our way stiffly off the airplane. A bitterly cold arctic night greeted us, the wind stinging our unprotected faces with specks of icy snow. One of my shopmates assigned to the ADVON team waited impatiently at the bottom of the ladder for us to clear off the aircraft so he could get to work. (ADVON stands for advanced  echelon).

echelon).I stopped a moment and yelled a question to him over the racket, “Dwight, what’s broken on this bird man?” Dwight Turner, a giant of a black man, was wearing a parka and mukluks; even so, he looked miserable. I could tell all he wanted to do was to repair the plane and get back inside to a warm room. (I have an interesting story about Dwight that I’ll tell in a future installment).

“The aircrew called in a fried number 2 compass amplifier. I’ve got a replacement amp r

ight here. Hopefully this’ll fix it,” he spoke in my ear above the loud engine noise of the power unit running not 20 feet away. I nodded, telling him that I’d see him when we all arrived in England. Dwight’s job with the ADVON team was to repair the instrument and autopilot systems on any of our aircraft that broke on the way across “the pond.” The ADVON folks then board the last aircraft and become “ordinary” workers like the rest of us when they get to the TDY location. At that point I didn’t give my broken airplane another thought, but it wouldn’t be long before that bird is ALL I contemplated!

ight here. Hopefully this’ll fix it,” he spoke in my ear above the loud engine noise of the power unit running not 20 feet away. I nodded, telling him that I’d see him when we all arrived in England. Dwight’s job with the ADVON team was to repair the instrument and autopilot systems on any of our aircraft that broke on the way across “the pond.” The ADVON folks then board the last aircraft and become “ordinary” workers like the rest of us when they get to the TDY location. At that point I didn’t give my broken airplane another thought, but it wouldn’t be long before that bird is ALL I contemplated!Mildenhall Sucks!

After the group of us from Little Rock arrived at Mildenhall the next day, we spent MOST of

that first day processing in. It was October 1987, the Cold War was in its last handful of years, but we trained and prepared as if the Soviets were about to attack us at any moment. We drew chemical warfare suits and attended classes on local flightline driving conditions and procedures, as well as guidelines in case war started. To make things even more interesting, Mildenhall was about to start an Operational Readiness Inspection, or ORI, and we were told we were going to have play along with them.

that first day processing in. It was October 1987, the Cold War was in its last handful of years, but we trained and prepared as if the Soviets were about to attack us at any moment. We drew chemical warfare suits and attended classes on local flightline driving conditions and procedures, as well as guidelines in case war started. To make things even more interesting, Mildenhall was about to start an Operational Readiness Inspection, or ORI, and we were told we were going to have play along with them.In short, we were going to be subjected to long arduous hours while wearing hot chemical protection suits and masks, and we weren’t the least bit happy about that! In fact, we were furious, especially when we were told that there would be NO days off for the duration of the ORI! We couldn’t believe they were taking away our liberty for 3 weeks—how dare

they!

they!Our argument was that if Mildenhall people had found THEMSELVES TDY to Little Rock, WE wouldn’t have made THEM play in OUR exercises; and it’s true—they would have been exempted. It was a stupid argument though, because if we had thought about it, we NEEDED to be as prepared as we could in case WWIII ever DID start; after all, when it came, it was going to be right THERE in Europe. Can you blame us though? All we wanted to do was work our “3 days on—3 days off,” and spend our liberty hours exploring England and Western Europe.

It took us nearly the entire day to in-process so that we could start work and get into our work and time-off routine. We were to work out of the Mildenhall Instrument/Autopilot Shop, and it was soon apparent that the shopchief was a hardass AND fond of chicken shit. He and I immediately decided that we didn’t like each other, when during a practice alert; he reamed my guys and me for not reacting fast enough when we were supposed to “hit the dirt” when the air raid siren sounded. I guess he wanted to make sure that we understood that HE was boss. As he scolded us, I stood there with cocked head and folded arms; and as he ended his tirade I shook my head in disgust saying, “Okay boss, if you say so.”

The first thing I learned from this jerk was that the bird I had flown in on was STILL broke. His guys had given it a shot over the last night and that day, but with no luck. I went back to the barracks that evening, knowing that my best man would be working it. I fully expected to find the malfunctioning #2 compass system fully up and running when I came to work the next morning for my first 12-hour shift of the deployment.

"Bad Boys" in The Galaxy

That evening, after dinner at the chow hall, I decided to check out the enlisted club, called The Galaxy, with a couple of buddies from Arkansas. Like most overseas military clubs it was packed with people. The slot machine room was cacophonous with the sounds of handles pulling, drums spinning, machines ringing, and coins a spitting as many of them paid off. The ballroom was rocking with a live band, and the smaller lounge where we ended up, had a DJ playing dance music. The lounge was crowded, yet strangely enough, there were two empty tables near the small dance floor, so that’s where the three of us headed.

Once seated, I couldn’t help but notice a table right next to ours with two young guys sitting nonchalantly. What caught my eye was the pile of ice cubes spread out under their table and beneath their feet. It looked like someone had dumped a bag of ice under there. Then we noticed the tension in the room. ‘Oh hell, what have we got ourselves into now?’ I thought. At first, it appeared that everyone in there was looking at us, but I soon realized they were scoping out the two guys with all that “ice” under their table.

One of two young fellas got up and headed toward the door. Just as he reached it, a sturdy dark-haired man wearing a blazer intercepted him, grabbed his arm and firmly led him out of the room. I looked at the ice and saw that it wasn’t ice at all; it was actually broken glass. Now that was weird! The young hooligans had been stomping their drink glasses into shards and bits under their table. There must have been two-dozen broken glasses under there.

The guy in the blazer returned. He stood with arms crossed, looking like a cigar store Indian, just ten feet from the last of the glass-breaking idiots. I got the feeling that there had been more than just two of these dumb-asses, and we were just catching the end of the escapade. The stern-faced “Blazer man” must have lassoed them one at a time, as I saw him just do. Everyone in the bar watched to see how it was going to play out with the last guy, and now, just my luck, I had a front row seat. I realized then the reason WHY our seats were available in the first place, and now I was going to be right on top of the action, IF there was going to be any. Our drinks arrived and we settled in for the “last act.”

“Blazer guy,” a medium-sized Latin fellow, was an American airman, whom I learned later was a staff sergeant with the U.S. Air Force security police. His job as a bouncer was a sideline. After ten minutes of standing with arms folded directly in front of the youthful miscreant—who continued to sip his drink as if everything was fine and dandy—the grim-faced bouncer approached him. It was a surreal scene with disco music blaring, and all the patrons watching intently as if checking out the finale of a show.

The bouncer stopped next to the man and leant over to speak. He got out no more than a few words when the troublemaker erupted. He sprang from his chair bringing his heavy-bottomed whiskey glass down full force onto the top of the cop’s forehead. The bouncer-cop crumpled to his knees as blood ran in rivulets down his face. His attacker didn’t see the results of his assault, because he was already sprinting toward the door.

He got nowhere in his bid to escape. One observer stuck out a foot and tripped him while three other guys jumped on his back, and none to tenderly. Amazingly, the bouncer quickly recovered and took custody of the crazy kid. He put the guy in an arm lock and walked him on his toes outside to a waiting police van. I spoke to the bouncer the next night and congratulated him on the good work. I asked him what the heck he was doing back on the job already, pointing at the large Band-Aid on his forehead. “All in a days work my man!” he answered cheerfully. Stuff like that is why I used to LOVE going on temporary duty—it was NEVER a dull moment!

It was STILL Broke!

The next morning I took “turnover” from my nightshift guys. I was disappointed to find out that the C-12 compass was STILL out of commission on the C-130 I had flown in on. For some idiotic reason, someone decided to try to change out another amplifier. Ten minutes after they applied power, it burned up in a small cloud of black burnt-transformer-smelling smoke. I was angry and let them know it! “You realize that that is the THIRD amplifier we have toasted on that bird? What were you thinking?!”

We had a real problem. Each time we wasted an amplifier it cost the taxpayer anywhere from 10 to 20 thousand bucks. I learned later that even though aircraft components are sent back to an Air Force depot for repair, they charge the responsible unit a set price for each one, no matter what is wrong with it. Even worse for us—there were no more amplifiers on station. Supply was going to have to get us another from wherever one might be cached in the supply system—in Europe if we were lucky. I called a meeting of my night and day shift workers with the express purpose of laying down the law. “Guys, you will NOT put another amplifier into that rack, UNTIL we know what’s causing them to fry. Is that understood?” They all nodded glumly.

Here was our quandary: We simply could NOT waste any more amplifiers, which is what we did every time we installed one and applied power to it. After 10 minutes, it’s power transformer heated up and exploded in a puff of pungent smoke. In the past, when that particular transformer burned up, it was because of shorted wiring INSIDE the amplifier itself. This time, there was certainly shorted wiring SOMEWHERE, but it WASN’T in the amp. WE had to find out where. The short could be in the several hundred feet of wiring, in the score of electrical connectors, or in the half-dozen C-12 compass components, or even in the handful of associated systems that received inputs from the C-12. We needed to find out WHERE the hell the bad wiring was, and we needed to find it SOON!

The C-12 compass system, the primary navigation equipment on the C-130 at the time, works by using a magnetic azimuth detector, or MAD, located in each of the aircraft’s wingtips. The #1 MAD, for the #1 system, is mounted in the left wingtip, while the #2 is in the right. The MAD produces a mili-voltage by reacting to the earth’s magnetic lines of flux, which run north and south through the earth’s magnetic north pole. Basically, it operates on the same principle as a handheld compass, where the little needle points north. Back then, before Inertial Navigation Systems and Global Positioning Systems, if any one of the two C-12 compass systems did not operate properly, the aircraft was forbidden to fly in Europe or over water. Thus, until we could fix it, that huge C-130E cargo aircraft was grounded. The pressure was on!

Besides our “problem child,” we were responsible for all our other C-130s as well. I assigned one of my technicians to pull the five primary system components composing the #2 compass. I wanted every one of those parts checked in the shop on the C-12 bench tester, that way we could be assured that all components were working absolutely perfect. Much of troubleshooting is a process of elimination, and I wanted to eliminate ALL the obvious possibilities first. We didn’t have much choice, except to do the bench checks, since without an amplifier; we couldn’t check out the compass “boxes” on the aircraft. I was worried that we might damage the bench tester, but as long as the shopchief let us do it, then thank you very much SIR! I don’t think it occurred to him that we might destroy his tester worth easily more than 100 grand—that’s dollars!

It took us the rest of that day and the following night for my guys to pull the parts from the aircraft and check them out in the shop, one at a time, using the strictest of the bench check procedures. The idea was NOT to leave any potential problem unfound. I arrived at the shop early the next morning hoping to hear some good news, but it was not to be. Every box worked perfectly on the bench. The only possible cause now, we figured, was wiring, connectors or associated systems. As much as I didn’t want to, from that point on, I put MYSELF on the problem bird, at least for MY 12 hours of dayshift.

.

By this time, the aircraft had been grounded for going on four days. It was becoming a monster and now it was MY monster. I felt queasy just thinking about it, and I thought about it a lot. When an Air Force aircraft, needed for missions, becomes “hard broke,” and stays that way for more than a day or two, a lot of high ranking people become very concerned. They want immediate answers to this question—WHEN is it going to be FIXED? That’s where the shit comes from, and boy does it ever ROLL downhill; and guess WHO was at the BOTTOM of the hill!

.

A “permanent party” guy, drove me out to the parking spot in the shop’s Mercedes stepvan, of all vehicles, where my “naughty airplane” awaited. On the way out, he pointed to one of the hard stands as we drove slowly by, where C-130s have been parked on that base for decades; he told me solemnly, “That’s the spot where a crazy crewchief took off in a C-130 trying to fly himself back to the States.”

I had never heard that story before, and it sounded intriguing. “Oh yeah? Is that true? It sounds like one of those modern urban legends to me,” I asked doubtfully.

“Oh yeah, it’s totally true. They say he was a sergeant, a crewchief, and he knew enough about flying to crank up the engines, taxi it off the spot to the runway and then into the air. They say he was having problems at home back in the states; he was here on a rotation just like you are. The story is he got drunk, filled up the fuel tanks, and took off before anyone could stop him.”

“No kidding? That’s unbelievable! No way man… How long ago was this supposed to have happened? How far did he get, back to the States?”

“I’m not sure when it happened, maybe 15 years ago, in the 70’s I think. I hear he got the plane over the water and the Air Force brass ordered some fighters to go up and shoot him down. They were probably afraid he would crash it into some civilians.” He shook his head, smiled, and went on. “That’s why all our birds are tied down and locked to the ground, and after he pulled that fool stunt, the Air Force prohibited all enlisted men from doing taxi checks.”

I cocked my head, “Oh man! You know, that DOES ring true dude. I always wondered why we have to use pilots to do taxi checks. I believe the navy lets their enlisted guys do those. It all makes sense now.”

My “guide” explained further; “The stand where he took off from, I swear, it’s haunted! Power units are always messing up on it; and lots of times when aircraft are parked there, their lights will flicker for no reason. Seems like strange stuff always happens on that stand. I HATE working there, especially at night.”

.

Danny Medina: "Save me!"

He dropped me off at my bird. I had a couple sodas in my knapsack to keep my energy level up, plus I carried a small avionics toolbox and a multimeter. And of course, I threw my “A” bag on the ground near the crew entrance door; it was loaded with my chemwar gear and my helmet, just in case the ORI kicked off while I was out there. A dark-complected, slender sergeant approached me from the plane, wiping his hands with a rag; I assumed he was the crewchief, and I was right. He nodded grinning, and introduced himself, “Hi. I’m Danny Medina. You the man that’s going to fix my airplane and SAVE my life?”

“Hi Danny,” I said shaking his hand. I grinned back at him asking, “What’s this about saving your life?”

“This is MY aircraft. I am assigned to it for the duration of the rotation. I’m supposed to be flying on it, and INSTEAD, I’m stuck here at “Moldyhole” until you fix the damned compass. So how ‘bout it?” (Moldyhole was our nickname for Mildenhall. We called it that because it seemed to rain there all the time).

“Okay, I get it, but how is fixing this plane going to save your life?” I laughed.

“Because I drew a couple thousand bucks advanced per diem (travel allowance) for this 90-day “rote” (rotation), and if all I do is sit here, I’m going to have to pay it all back. That’s going to suck man! I’m LOSING money even as we speak. You’ve got to help me out!” he pleaded.

“Roger that Danny, but first lets ask her where she hurts, shall we?” I walked up to the C-130’s big bulbous nose, or radome,” and gave it a big hug with my arms outspread and then solemnly chanted the traditional C-130 maintainer’s verse, “Herky, Herky, big and fat; tell me where your problem’s at!”

“Roger that Danny, but first lets ask her where she hurts, shall we?” I walked up to the C-130’s big bulbous nose, or radome,” and gave it a big hug with my arms outspread and then solemnly chanted the traditional C-130 maintainer’s verse, “Herky, Herky, big and fat; tell me where your problem’s at!”We both laughed, and I told him, “Okay Danny, time to get to work. I take it you don’t mind giving me a hand? I could sure use it.”

“Man! Whatever you need me to do, just tell me. I’m your guy. Let’s fix this damn bird so I can get back to flying in it!”

Buckling Down

First thing I did was to break out a notebook from my knapsack. With Danny for company, I went through the aircraft forms and noted any and all maintenance that might have anything at all to do with the #2 compass. I looked for clues to the problem, plus I didn’t want to repeat any work that might have already been accomplished; also I searched for any basic aircraft electrical problems that might have had some kind of negative affect. I decided that our next step was to start checking the wiring—first at the connectors, then at junction box connections, and finally, all of the wiring runs. It was a daunting task, but it needed to be done.

Danny and I used my notebook to record each wire—connector-by-connector, wirebundle-by wirebundle—that we checked out with the multimeter. Because the transformer took ten or so minutes to heat up before finally burning up, no fuses were blowing and no circuit breakers were tripping. This was a hindrance, because we had absolutely no clues to point us to a possible culprit. The one thing I was sure of was that we were dealing with a high-resistance short, meaning we had at least two wires interacting electrically that were supposed to be isolated from each other. The only way to find it was to use the ohmmeter mode on my multimeter. We were going to have to check for shorts in each run of wire, not only from point-to-point, but also to ground, and to other wires around it. The possibilities were almost endless.

Another problem with working electronics on aircraft is vibration. The four engines of the C-130 make the entire platform, and everything on it, buzz and vibrate at the very least, and in the turbulence of flight it’s much worse. So, while I checked my continuity readings I had Danny shake and move the wire-bundles as much as he could, so we could simulate as much as possible the actual conditions of flight. To say it simply—working airplanes ain’t easy!

Staff Sergeant Stewart Smart, my best technician, relieved me at the airplane that evening just after 7 p.m. I gave him my notebook, in which I had tracked all the wiring runs as we had checked them out. After all those hours of peering at tiny pin designations on the connectors and studying the schematic for the compass system, when I closed my eyes, I was seeing wiring diagrams on my eyelids. Wearily, I wished SSgt Smart good luck and told him, “Stew, please fix it. This thing is kicking my ass!”

He answered me cockily, “No problem mate. I’ll have it fixed in a jiff. Piece of cake!” Stewart was a real Englishman, with a clipped moustache to boot, serving in the US Air Force, and he had all of us “yanks” saying, “mate.” He was pretty cool—for a Limey that is! I knew if anyone could find out what was wrong with “problem child,” it would be Stew. He was definitely the sharpest Instrument troop I had, so I hoped against hope that he would take ALL the “glory” and find out what was wrong with that damned compass.

"Sacrificial Amp"

My heart sank the next morning when I walked into the shop at 6:30. Stew sat wearily in the break room sipping his coffee. “Morning Stew,” I ventured. “What did you find, anything?”

“PJ,” he started, “we checked every wire, some twice, and came up with zeros. We did find a couple wires that seemed to have high resistance readings, but I wasn’t sure if they weren’t within limits; so we checked the same wires in the number 1 system, and they read about the same. But, I do have ONE bit of good news for you mate.”

I perked up, “Oh yeah? I can USE some good news about now. Lay it on me mate.”

“Well, we had another C-12 problem last night on a different aircraft. We found it had a bad amplifier; its synchronization module is “tits up.” So! That means we have an amplifier that we can use for troubleshooting our problem bird. The amp is already broke, so we won’t be hurting anything when we burn up its transformer.” He stood up stretching and said with a groaning sigh, “Hey, it’s not great, but it’s something.”

He was right. Now we had a “sacrificial amp,” as I named it, that we could use, hopefully, to find out what had caused all those other amplifiers to fry. I prepared myself for another long day way out on the other side of the flightline, basically in the middle of nowhere, and felt an unpleasant weight on my shoulders and a heaviness in the pit of my stomach. To make things worse, the grouchy shopchief, “my buddy,” called me over saying, “Sgt Spear, can I speak to you?”

‘Oh boy, here we go!’ I thought. Sure enough, he added to my woes. First, he reminded me that it had been more than five days, and we STILL had no idea what was wrong with our airplane. He wanted to tell me that there was a lot of grumbling from the “brass” about it, and they wanted that plane flying NOW! Furthermore, he told me that he expected the exercise to start in earnest soon. That meant worrying about war condition indicators that would have us putting on chemwar suits, and at times taking cover inside the many sandbag bunkers located all around the flightline.

I clenched my teeth thinking, ‘Man that sucks! That’s ALL I need to make my day complete!’ I doubted if things could get any worse, but all I said to him out loud was, “All right, well let me get to work then.”

A New Plan

Danny met me at “his” aircraft and I greeted him, “Morning Danny. Hey, I’ve got good news for you.”

He brightened up, “Really? Did you guys figure it out?”

“No, but we’re going to try something different today, and hopefully, we’ll finally get this pig fixed.” I explained about the sacrificial amp and how we were going to try to use it to find out what had burned up the power transformers.

“So, here’s the plan Danny: What I want to do is to pull every related circuit breaker and fuse, and disconnect every component from not only the compass, but also from all associated systems that have any inputs at all from the #2 compass. Then carefully, using lots of forethought, I want to push in the circuit breakers and fuses, and reconnect each component, all slowly and one-by-one, until this sacrificial amp smokes. Here’s your job Danny, if you choose to accept it,” I said jokingly: “I want you to sit at the top of the ladder, so your nose is right on the sacrificial amp. That way, as soon as it goes up in smoke, you’ll be able to tell me the exact moment, and so what component or system is causing it. Does that make sense?”

“Yeah, I can do that. No sweat!” He answered cheerfully, “It sounds like a good plan. I have a good feeling about this!”

“All right, but I have to warn you, you could be up on that ladder for a LONG time, because we have to do this slowly and deliberately. We are going to have to push in about 25 breakers and fuses, one at a time, and then reinstall connectors and components in the same way. But to make it worse, we need to wait about 20 minutes after each action to make sure we don’t miss what exactly causes the amp to fry. Do you think you can handle that?”

Danny didn’t skip a beat, “Hey, let’s get to work man. Time’s a wasting and I’m losing money RIGHT now! You tell me what to do, and I’ll DO IT!”

We were about 20 minutes into getting the aircraft prepared when we heard the maintenance van insistently honking outside. “Danny, find out what’s happening!" I yelled from the flight deck. Glancing out the plane’s window, I could see it flying a yellow flag. That meant the war games hard started, so it was time to suit up and break out our helmets and gasmasks. ‘Oh well, war is hell!’ I joked to myself.

After putting on our ensembles and placing our gear nearby in the event of a higher level of mock war, such as an attack, we got back to work. It took more than an hour to map out in my notebook all the components, breakers, fuses, and connectors that we would be reinstalling and energizing. I needed to do this task in a logical order, or it would be futile. For instance, what good would it do to power up the Doppler, BEFORE I had power applied to the compass? If I actually DID have a back voltage coming in from the Doppler, I would NEVER know for sure, if the compass wasn’t even put together yet and powered up. In light of this, I had to do SOME reconnections in various orders and configurations to make sure I covered as many different possibilities as I could think of.

.

...and War Games TOO?

We were just starting to put my plan into action, when we heard the alert siren start to wail the signal for condition red—we were under attack! I yelled at Danny who was already running out of the aircraft to turn off the power unit. We pulled on our gas masks and helmets, gathered the rest of our equipment and sprinted for a bunker about 40 feet away from the nose of our aircraft. As we crouched inside the sandbag shelter we made final adjustments on our equipment, tightening up our masks, smoothing down each other’s mask hoods, and pulling our sleeves and pants down fully over our rubber gloves and booties. Five minutes later we were sweating like crazy inside our masks, even though it was relatively cool outside at 55° F. Danny cursed impatiently, “Damn it! We’re wasting time out here man!”

I shrugged resignedly and joked, “What can we do man? War is hell!”

He was right though. We wasted over an hour sitting and laying there on the grassy ground inside the shelter, while we waited for the condition to go back to yellow so we could get back to work. We peered out of the bunker when we heard the siren go to yellow, but to make sure, we waited until we saw an Air Force vehicle in the distance flying a yellow flag. “Let’s get back to work Danny,” I declared unnecessarily.

“No shit!” he said in disgust.

We went back to work with a vengeance. Unfortunately, by necessity, it was slow and tedious, and we couldn’t hurry it. I followed my plan methodically, pushing in a circuit breaker then telling Danny, seated seven feet up on the top step of his metal folding ladder, to start sniffing for smoke. After 20 minutes, I would put another component or system into play and Danny would start sniffing the amplifier again, until another 20 minutes had passed. After 10 cycles of doing this, I started to get excited. I got the feeling that today would indeed be the day we were going to finally solve this difficult mystery.

Hours went by. It was late in the afternoon, and we were down to only a few components left to reconnect and try out as part of our routine of: connect—power up—and sniff. As we came to the end of our gambit, Danny took a break to have a soda with me on the flight deck. He observed, “PJ, this thing is almost back together and it’s STILL not smoking. What do you think man?” he asked.

“If I had to guess, I’d say that maybe we fixed it by chance when we disconnected and reconnected all those electrical plugs and all those components. Sometimes it goes like that. Avionics can be baffling and mysterious dude. I think this job at times is more magic than anything else. But, who knows, we’re not done yet. You ready?” He nodded and we continued—with him on his ladder, and me on the flight deck after reconnecting another component.

.

A DOOZY of a "MAD!"

It was going on 5 pm, and we had just one part left to reconnect—the #2 MAD, out in the left wingtip. I called to my collaborator, “This is the last one Danny. Cross your fingers!”

“Okay PJ!” he yawned, “Do you think this is it?”

“We checked the Flux Valve out in the shop, so I don’t see how this can possibly be the problem. Anyway, stand by; it will only take a moment to spin on the plug and push in the circuit breakers.”

“Roger that!” he answered excitedly without a trace of fatigue in his voice.

I pulled myself up through the forward hatch and onto the topside of the C-130. I walked gingerly along the spine, turned left where the wings joined the fuselage, and made my way out to the very end of the wing. I knelt and spun the connector tightly into position. I dropped back through hatch and announced to my dependable assistant, “Danny, I’m pushing in breakers. Heads up!”

“Go for it man! I’ve NEVER been more ready!”

I squashed in the #2 compass breakers one at a time with my right thumb pad. Each one made a telltale SNAP as it set into the energized position. “That’s it. They’re all in. Start sniffing!” I announced.

Seconds, then minutes passed, two minutes, then three. After 7 minutes I called out, “Anything?” He didn’t answer so intense was his concentration. I saw him hunched over the amplifier, staring at it intently. I had to maintain my position on the flight deck, so I could pull breakers immediately as soon as any smoke or flames became evident. The strain was enormous as I waited. Then, at the 9 minute mark, Danny practically screamed, “It’s smoking! That’s it man! We found the problem!”

I de-energized the compass and sat down heavily on the lower bunk in the rear of the flightdeck. As unlikely as it seemed, the #2 Magnetic Azimuth Detector, a part we also called the Flux Valve, was bad after all. ‘How could that be?’ I thought. We had checked it on the bench and it was fine. But when I thought about it, it made sense. The MAD contains hundreds of feet of tiny windings made of insulated copper wire, and these windings MUST have developed a very high resistance short. ‘It must be a malfunction that cannot be checked on the bench tester,’ I surmised to myself. It was one of those unlikely anomalies that technicians run into about once every year or two, and this one was a doozy!

I de-energized the compass and sat down heavily on the lower bunk in the rear of the flightdeck. As unlikely as it seemed, the #2 Magnetic Azimuth Detector, a part we also called the Flux Valve, was bad after all. ‘How could that be?’ I thought. We had checked it on the bench and it was fine. But when I thought about it, it made sense. The MAD contains hundreds of feet of tiny windings made of insulated copper wire, and these windings MUST have developed a very high resistance short. ‘It must be a malfunction that cannot be checked on the bench tester,’ I surmised to myself. It was one of those unlikely anomalies that technicians run into about once every year or two, and this one was a doozy!I caught a ride back into the shop and asked if they had a spare Flux Valve in the

shop, so that I could verify the faulty one on the plane. They didn’t, so I ordered one. It was delivered in a few minutes and I took it out to my C-130. Danny was still there, and he walked out on the spacious wing with me as I set the new MAD into its mount and tightened on the electrical plug.

shop, so that I could verify the faulty one on the plane. They didn’t, so I ordered one. It was delivered in a few minutes and I took it out to my C-130. Danny was still there, and he walked out on the spacious wing with me as I set the new MAD into its mount and tightened on the electrical plug.“One last thing before we can be sure right?” he queried me hopefully.

“Yup, let’s go power up this baby.” Without fanfare, I pushed in the circuit breakers that applied power to the #2 compass. Danny went back out to his seat on top of the ladder and waited. After 15 minutes I knew we had nailed it. Danny and I shook hands in a quiet anticlimactic celebration.

“So what’s next,” he asked?

“It’s going to take at least another 8 hours to align, install and calibrate the new flux valve. Don’t worry man, by tomorrow morning this bird can be in the air.”

Ecstatic, he said, “Thank God! Finally! Man, what a RELIEF!

Blackbird!

Just then, we heard a deep rumble that shook us all the way to the core of our bones. We knew immediately what it was—an SR-71 Blackbird! Bonus! We scrambled back out on top of the plane for a better vantage point. The pilot of that awesome beautiful black rumbling monster must have felt like a movie star, because virtually everyone he passed was standing, watching and waving at him. He was a great guy, because he waved back at each and every one of us.

.

The Blackbird was amazing to see, even as it taxied out to the end of the runway; but when its rumble deepened and became even more intense as it rolled off on its way to take off, it was absolutely thrilling. In no time at all that incredible black vision roared high into the sky and was immediately lost in the low gray clouds of the misty English evening sky. I smiled at Danny remarking, “Great way to end a PERFECT day, eh?”

"SR-71 Blackbird!"

Good Show!

It turned out that I had enough time to take the Calibrator Set out to the Compass

Swing area and start to set up all of its extensive equipment. Stew met me out there in the gathering darkness. Uncharacteristically for him, he had a huge grin on his face, obviously happy that I had solved our compass problem. He greeted me with a hearty, “Way to go PJ! You figured it out. Good show mate! Tonight, YOU are MY hero!”

Swing area and start to set up all of its extensive equipment. Stew met me out there in the gathering darkness. Uncharacteristically for him, he had a huge grin on his face, obviously happy that I had solved our compass problem. He greeted me with a hearty, “Way to go PJ! You figured it out. Good show mate! Tonight, YOU are MY hero!”“Thanks mate,” I grinned. “I have to agree with you. At this point, I’m MY hero too! I’m outa here man. I can’t believe how tired I am!” I declared wearily.

But it was NOT to be. Before I could get away and back to the “safety” of my barracks room, the air raid siren went off sending us all to condition black. “Damn it!” I yelled in frustration as I scrambled back to my “A bag,” pulling on my gas mask and helmet.

That night, more than two hours after my shift supposedly ended, I finally got back to my room. Another day, another dollar! Just goes to show you though--that it's the tough jobs, done well, that become seared into your memory, even after almost 20 years!

16 comments:

Excellent story. I've spent lots of time hunched over some wiring trying to trouble shoot it with a multimeter and after reading this story, I know I can't start complaining unless it takes at least four days.

I remember touring a Boeing shop in St. Louis and seeing a 747 with the wings off. What was left was a fuselage with a rainforest of wires hanging down. It is a sight that continues to haunt me everytime I fly. How they get hooked up properly, I'll never know.

Love the picture of the SR-71 taking off!

Yeah Ed, when you glimpsed the "guts" of that 747 you really got an idea of the complicated nature of aircraft. Although it looks much worse than it is when you see one like that. During aircraft assembly, these days the procedure is normally to install pre-built wire bundles for entire systems, many times already complete with connectors.

But you are correct that what maintenance professionals do to to build and maintain aircraft systems is very impressive. You'd be surprised how many things are actually broken and malfunctioning on aircraft, even the commercial ones you fly on. That's why all the important systems are dual and even triple redundant.

The SR-71 was an amazing bird. To this day, NO one has come close to building an aircraft that could fly as high AND as fast. The Skunkworks guys who built it in the late 50s and early 60s are engineering gods! I'll never forgive Cheney for killing it in the early 90s. He made a huge mistake.

Have you ever read the book "Skunk Works" by Ben Rich? It was a fascinating look into the design and building of the F-117A Stealth Fighter. As an engineer, I marvel at how they tackled and solved problems.

Ah so, you are an engineeer. Now I know. Yeah, i read that book. Too bad he died so soon aftr it was published. If you get a chance, reread his final chapter. He practically predicts pretty much everything that is going on right now in the world.

I got the chance to work for one week with the engineer who designed much of the avionics, especially the original C130 autopilot. His name was Big Al. They brought him out of retirement and sent him out to us at Yokota AB to figure out an "unfixable" autopilot. If anyone likes this story, I'll tell that one. I remember how much he enjoyed getting his hands dirty with us maintenance guys...he said he hadn't been allowed to do much of that "hands on" stuff when he was at Lockheed. It was a privilege working with Big AL. And man, did he ever have some stories to tell!>.........

That's what I'm talkin' about! Great story. This is the same, but different. When I toured Buick city in Flint (back when they still made cars in Flint) The tour guide said that if the wiring harness was incorrectly installed on a car, it was cheaper to scrap the car and start over rather than try to fix it.

There is an SR-71 on display in Kalamazoo now. Pretty cool. When I was there, they had one of the engines out of it and on display in a different hangar while they were restoring it. Amazing.

Cheney killed that program? Didn't know that. Why? satellites? Or maybe something new still classified?

This is one great story (and the longest post I have read in my two years of blogging!). I have a technical background so I can understand some of the scenarios you narrated, and what makes this story all the more interesting are the other events surrounding the "problem child" like the war drill and the visit to the local bar. I am in awe of the life you lived serving the Air Force!

Hi Kev,

It's true--once wiring is in an aircraft it is TOUGH beyond measure to repair, and almost impossible to replace. When I was a project officer at Little Rock, one of my jobs was to ensure that my contractors removed all the old wiring as they replaced it with new system harnesses. The hidden recesses and sharp, blind turns make it incredibly problematic to inspect, to repair, to replace, you name it. Basically, once it's in...that's it!

The AF tries to use that same civilian standard of "too expensive to repair, just buy a new one," but it's not feasible on military aircraft, not to mention it's NOT always true (that its too expensive to try). I'm proud of the fact that, as airman, we NEVER turned down a job because it was too "hard." And that's what that Buick guy was really saying, that it was too hard. We never had that luxury.

Yup, Cheney killed the SR-71 when he was SecDef. It was strictly an economic decision and it was shortsighted. That airplane could do things that we cannot do with satellites and it could do them with impunity. Thousands of SAMs, and air-to-air missiles were fired at it over the decades and the closest one ever got to it was maybe a mile away. Amazing. "Cheney! You idiot!"

Hey Wat:

Sorry about the length, but some tales just require it, especially when its me telling them. Glad you appreciated the human interest tangents. I had many other "adventures" during that TDY to England, but as you said, it was already "the longest post I have read..." (Although, my post "Climbing the Mayon Volcano" is probably longer, albeit in two parts).

Just the same, thanks for being patient and getting through it to the end.

Hello Ed,

If Kelly Johnson thought so much of Ben, so as to choose him as his successor, then you can bet that you are right: Ben Rich WAS a genius and not just as an engineer. His abilities as a manager AND his natural way with people turn out to be even more important than his engineering smarts. From what I read, it was also his persistence that made him so successful. I can really relate to that side of him, as you might see in this post. Ben Rich died in 1994...what a loss!

Nah, not too many 'normal' people want t read yer obsession with detail .. heh ;-\

Oh well ..

Hey great story Pj. Brought back a lot of memories of Moldyhole. I never remembered you being that organized though. The whole notebook thing sounds like Smarty. Urban legend??? Good seeing Dwight's name. I used to be bud's with him. We'd work out together at the gym and then go to the chow hall and eat like 6 eggs and bacon and toast and then he'd eat like a whole ham. Can't wait for your story about him. I've got a couple myself.

Mike,

how exactly DO you remember me? The whole time you knew me I ran one of the shifts, usually swings or grave shift. I wasn’t the strictest of supervisors, but my people always got the job done. Is that where you got this disorganized impression of me? Your comment puzzles me.

So you doubt my story eh? Hmmm. In Yokota, before I got to Little Rock, I worked several tough autopilot malfunctions on several types of aircraft; the two toughest were on a C-141 and a C-130. I learned there in Japan that a complicated system with a persistent malfunction required more than the old maintenance scheme of “Remove and Replace.”

You remember the term “shot gunning” a malfunction, right? ...just change out every part you can think of till you fix it. But, if that didn’t work, it meant it was time to actually think a problem through, and the only way to keep track of wires checked and procedures tried was to keep a notebook. Remember those green hardcover notebooks we used to be able to get from supply? Those were my favorite.

Stew was a good man and a great technician, but he was very distracted while he was there in Mildenhall. All he could think of, it seemed, was getting liberty and going home. He happened to be my roommate, but I rarely saw him. And nope, although he took over my notebook when I hadn’t yet finished checking all the wire runs, it was MY notebook and MY brainchild for that particular airplane. Anyway, it wasn’t exactly rocket science to keep some kind of record of what was done, and a notebook seemed like the obvious method.

Dwight Turner is a good man. He looked like he should be a badass, he was so big and black, but he was a teddybear. My little story about Dwight will come soon, so stay tuned.

Hey, when you going to start your blog. I’ll tell ya buddy...they are good fun!

Phil,

I was not serious about my last comment. Just busting your chops a little. I do remember you as being very thorough and doing great work. Hopefully your thoughts are the same for me on the instrument side of things. I remember you well. I thought the little urban legend tag would have let you know it was all in jest. Sorry you took it the wrong way. Getting back to Dwight my fondest memory was of us working out at the gym and he asked me to spot for him while he benched around 340 lbs. I asked him what exactly he thought I was going to do if he could'nt lift it. If you remember me back then, I only weighed around 160. It was a humorous moment. Now, some 20 years later, my weight would be a little more supportive. LOL

Hey Gam-Mike…I’m just a sensitive Sue! I’ve already had one guy question my veracity over one of my stories. I don’t write fiction and I don’t embellish, and least not since I wrote an Enlisted Performance Report in the AF as my last task before retiring!

Indeed, I remember that you were one of my “go to guys.” I wonder why we call them “urban” legends? When they happen in the suburbs and rural areas, we still call the “modern urban legends.” What’s up with that anyway?

Dwight loved the gym. I felt so bad for him when he came down with Lupus, but even after that he still managed to keep much of his size. Yeah, YOU were a lot smaller than you seem in your that picture in your realtor site photo. I have to put my thumbs on both sides of your eyes, and then I can say, “THERE you are!” Ever watch the movie “Hook” with Robin Williams when the little boy does that and says it to the grown up Peter Pan? There you are Mike…!

Hey!

I started reading through your blog. I laughed so hard at the maintainer chant!! The term for in-depth troubleshooting is "troubleshoot to other than LRU" these days. The majority of the guys d/n realize that something other than a LRU will cause malfunctions. I truly believe the reason most d/n want to use a meter is they're scared of getting zapped. HA! A few years back I was called by another AMU to fix a recurring HSI w/n work in TACAN malfunction. I read all the turn-over for the past 2 weeks and went out to tackle the problem. Eyes popped out when I stuck my arm behind the instrument panel w/ power on to shake the HSI cannon plug. See no one could duplicate the discrepancy on the ground until now. In less than 15 minutes I had troubleshot it down to a cannon plug. It took awhile for the environmental plug to come in. I refused to order the solder type because these people can't solder for anything. As it turns out they can't change an enviromental plug for anything either. I was called back out a week after it's first flight because it now ONLY worked in TACAN and not in any other mode. Picky!! Picky!! Avionics technicians had exhausted their troubleshooting skills and needed help. Like the true specialist I am I told them to have a meter and the wiring diagram waiting for me when I got out to the aircraft. I went to the last place maintenance had been performed and metered the HSI cannon plug. It turns out that the wrong diagram had been used to replace it because the technician d/n use the TOPS page when connecting the MLS wiring. These "extra" wires were inserted where his fancy had struck at the time and the plug was dorked even further because wire maintenance is NOT their forte. When the plug had been replaced before they actually just replaced the plug and it was shorter than the shortest hair on a human body. So I ordered ANOTHER plug, built it up and spliced it in myself. Swap-tronics isn't the norm w/ everyone!!

Hi Tanker...

Yep, the C-12 tester does have several pages of benchchecks for the flux valve (MAD). Its not in the book to do, but we simply drew a pencil line around the MAD so that we could drop it directly back in from whence it came. Believe me, it works good and lasts long time.

During my 7 actual manintenance years on C-130s I probably accomplished at least 30 compass swings, and also did another half-dozen or so of the even more complicated compass surveys, which had to be reaccomplished on the compass rose on an annual or semi-annual basis.

From what i understand compass swings are a thing of the past. A C130 job guide came out that allows a techy to "swing" a compass using the Self Contained Navigation System. And with the prevalence of GPS and the accuracy of the new Inertial Nav Systems I'd be surprised if any of the old magnetic compasses still exist... and truthfully, good riddance!

Post a Comment