This two-lane cement road closely follows the eastern side of the Cagayan River. The ride north was pleasant with wonderful views of the wide river and its valley to the left, and vistas of gently rolling hills to the right. Both sides of our vehicle offered pastoral scenes of wallowing carabao, and well-tended fields of tobacco, corn, and rice. The steeper hills are heavily vegetated with bananas, mangos, palms and all sorts of other hardwood tropical trees. On the whole, I decided that its one of the most serene looking places I’ve yet seen in this country. The towns and villages pop up every ten or fifteen minutes of travel, and they are uniformly clean and well kept. I was impressed; Cagayan looks like a nice place to live.

This two-lane cement road closely follows the eastern side of the Cagayan River. The ride north was pleasant with wonderful views of the wide river and its valley to the left, and vistas of gently rolling hills to the right. Both sides of our vehicle offered pastoral scenes of wallowing carabao, and well-tended fields of tobacco, corn, and rice. The steeper hills are heavily vegetated with bananas, mangos, palms and all sorts of other hardwood tropical trees. On the whole, I decided that its one of the most serene looking places I’ve yet seen in this country. The towns and villages pop up every ten or fifteen minutes of travel, and they are uniformly clean and well kept. I was impressed; Cagayan looks like a nice place to live.

Still thinking that our destination was Aparri, I kept looking for the South China Sea to show up to our front. After more than an hour, my heart sank a bit when we pulled off the Maharlika and into the dusty dirt of a gravel parking lot. ‘This is it?’ I thought gloomily. We had parked in front of a tiny, tattered L-shaped lodge, our home for the next week, I soon learned. More often than not, when we go on these “outreach trips,” its to a good-sized town or city, and usually we stay in one of the better tourist hotels. Things were going to be different this time. Oh well, as Doc always says, “We’re tough!”

I sat quietly in an easy chair in the lobby and listened as Doc chatted up the lodge owner. Our rooms weren’t ready yet. An older woman with some cleaning supplies was just about to do her thing and make them “fit for foreigners!” In the meantime, we made our way to a small diner at the far end of the lodge by the road, and sat together around a large wooden table. I wasn’t much in the mood for chow, but I ate a little rice and a Filipino dish consisting mostly of long beans and sweet potatoes, or kamoté as sweet potatoes are called here. We tried to pay, but our hosts refused our money.

Our rooms were large but spare. I was thrilled to see that the “important” items were there—a TV and an air conditioner—both as tiny as they come. My happiness was complete when I found Cinemax on one of the 10 available satellite channels. The proprietor, another one of Cherry’s relatives, was profuse with apologies about my room, especially as he explained that I would have to flush the toilet with a bucket; also, I would be showering out of that same bucket. And finally, I would be using Filipino toilet paper—aka soap and water! It’s times like that where my five years in the USMC serve me well; no matter how uncomfortable things get, I’ve always seen worse. But hey, I had Cinemax, so all was right with the world!

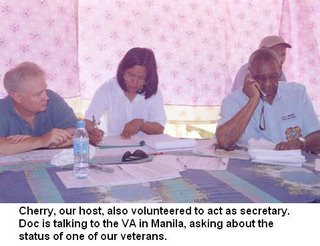

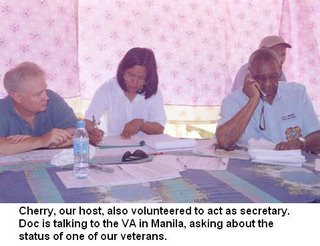

We were to meet our group of hopeful old veterans the next morning at 0730, so after breakfast Doc and I crammed into a trike and headed for Gatarran proper, only about a mile south of our hotel. At the far end of town we extricated ourselves painfully from our cramped transport and ambled down the hill to Cherry’s simple home. A large group of folks were already seated and waiting for us. We waved and smiled our hellos, shaking hands here and there like politicians. We took our places at a large table in front of the gathered seniors.

First things first, an elderly woman asked us to introduce ourselves, and then all the notables present were introduced to us. Then a prayer, part of which was aimed at us:

“…and lord, please ensure that these two kind and honorable gentlemen help us with our VA claims, especially considering that we faithfully served when the government of the United States of America asked us to put our lives on the line in the war against the cruel Japanese…”

‘Oh boy, the pressure’s on!’ I thought, grinning with cocked head.

One last thing before we started—a spirited rendition of the Philippine national anthem, and I must say, it sounded pretty good. Those old folks could sing!

One last thing before we started—a spirited rendition of the Philippine national anthem, and I must say, it sounded pretty good. Those old folks could sing!

After that, we interviewed each person one at a time. We saw more than 30 folks that first day. Most of their problems stemmed from not being recognized as veterans by the VA, or they didn’t have evidence that their current medical conditions had resulted from their time in service.

The ones that always break my heart are those with supposed “unproven” service. Many of these poor old fellas have reams of documents confirming their service, but since they didn’t get their names recorded in 1948 by the War Claims Commission, the VA refuses to recognize them as U.S. veterans. It’s one of the most un-American and unjust situations I’ve ever seen, and it makes me ashamed of my government. The only way to help these folks before they all die is to find an American legislator to sponsor and pass a bill to FORCE the heartless VA regional office in Manila to stop this faulty practice. I’m not holding my breath; I’ve written Carlos Pebenito, the guy in charge of the benefits section, and his response was typically bureaucratic and weak: “It’s the law, and NOT my problem. Oh, and good luck with that Phil!”

VA refuses to recognize them as U.S. veterans. It’s one of the most un-American and unjust situations I’ve ever seen, and it makes me ashamed of my government. The only way to help these folks before they all die is to find an American legislator to sponsor and pass a bill to FORCE the heartless VA regional office in Manila to stop this faulty practice. I’m not holding my breath; I’ve written Carlos Pebenito, the guy in charge of the benefits section, and his response was typically bureaucratic and weak: “It’s the law, and NOT my problem. Oh, and good luck with that Phil!”

After running across a half-dozen cases like that, Doc and I figured it was time for me to “speechify.” I got up and detailed to all those present what the problem was, and what I was trying to do to fix it. I also told them not to get their hopes up. Sigh.

After running across a half-dozen cases like that, Doc and I figured it was time for me to “speechify.” I got up and detailed to all those present what the problem was, and what I was trying to do to fix it. I also told them not to get their hopes up. Sigh.

The next two days went like that. We listened to each veteran, widow, son or daughter and examined their documents. Whether we had good news or bad, all were gracious and thankful that we had taken the time to come out and listen to their claims woes and queries. After listening to each, we told them exactly what kind of new evidence they would need to reopen old claims, or what medical proof would convince the VA that their current disabilities warranted an increase. Each case is different, and each one is important to us.

We met a remarkable 84-year-old woman named Atanacia, Cherry’s aunt. She invited us to come with her across the Cagayan River to see her home in the little town of Callao. In the afternoon, once Doc and I had finished mostly disappointing the majority of our clients, we walked out behind Cherry’s house to the banks of the river. Thing is, at more than 30 feet, it was more of a cliff than a bank, and it was in an alarming state of erosion. Cherry’s uncle, whom I’ll call “Uncle Doc,” because he’s a retired physician, told us that their house would probably fall into the river within the next couple of years. In typical accepting Filipino fashion, they shrugged off the impending doom of their home, and said they’d just relocate once the house was about to fall. Being long-suffering is both a Filipino blessing and a curse. I sure can’t be like that, but more power to those that can.

Callao. In the afternoon, once Doc and I had finished mostly disappointing the majority of our clients, we walked out behind Cherry’s house to the banks of the river. Thing is, at more than 30 feet, it was more of a cliff than a bank, and it was in an alarming state of erosion. Cherry’s uncle, whom I’ll call “Uncle Doc,” because he’s a retired physician, told us that their house would probably fall into the river within the next couple of years. In typical accepting Filipino fashion, they shrugged off the impending doom of their home, and said they’d just relocate once the house was about to fall. Being long-suffering is both a Filipino blessing and a curse. I sure can’t be like that, but more power to those that can.

Getting back to Atanacia, we told her we would meet her later that afternoon for the boat ride to the far bank. Just before 5 p.m., Atanacia and her brother met us at the boat landing. It was NOT what I had pictured. I figured there would be a fairly flat and  easily accessible way to the water. Instead, I was astonished to see another sheer 30-foot cliff.

easily accessible way to the water. Instead, I was astonished to see another sheer 30-foot cliff.

I asked Atanacia, “Momma,” as we called her, “how are we going to get down to the boats?”

“Down the stairs,” she answered matter of factly, pointing to the alleged flight of stairs. Sure enough, they were there—a series of steps carved into the hard-packed sand cliff. I hadn’t noticed them at first, so inconspicuous were they. I asked her how she could possibly go up and down that steep slippery-looking cliff at her age, and she told me she did it every day, twice a day. I couldn’t believe it; I wasn’t sure that I was even confident enough to do it. The cliff face is at least as high as a three-story building, and it looked quite daunting. “Momma, if you can do it, so can I!” I declared.

A 12-foot-long wooden skiff, the “ferry,” was heading back from the far bank with a load of a half-dozen passengers, so it was time to head down to the river. I watched Atanacia take the hand of a young man, and she followed him gamely down the narrow sandy sloping steps with barely a pause. He led the way and she steadied herself by holding his outstretched forearm with one hand, while balancing herself by holding onto the cliff wall with the other. She made it all the way down the series of three steeply slanting ramps of steps without a problem, so Doc and I scrambled down behind her. I tried not to look as nervous as I felt. I can’t imagine an 84-year-old American woman, or man, even considering such a feat. Incredible! One misstep and her brittle old bones would have splintered when she hit bottom. I shuddered at the image.

The Cagayan River is quite wide; Atanacia and her brother both told us it wasn’t always so. It seems that the rainy seasons now bring massive floods of water down from the mountains, no w much denuded of timber. In the old days, they said, the river ran much slower; it’s only been the last 10 or 15 years that the yearly torrents began to eat away at the edges of the river. They shook their wizened heads and blamed it on government mismanagement and corruption—a series of regimes unwilling or unable to control illegal logging; and without the funds or inclination to keep valuable farmland, and people’s homes, from being lost to the yearly erosive effects of ever-swifter-moving floodwaters. Sure enough, the river where we crossed it was probably a thousand meters wide. Uncle Doc said when he was a boy it wasn’t half that wide.

w much denuded of timber. In the old days, they said, the river ran much slower; it’s only been the last 10 or 15 years that the yearly torrents began to eat away at the edges of the river. They shook their wizened heads and blamed it on government mismanagement and corruption—a series of regimes unwilling or unable to control illegal logging; and without the funds or inclination to keep valuable farmland, and people’s homes, from being lost to the yearly erosive effects of ever-swifter-moving floodwaters. Sure enough, the river where we crossed it was probably a thousand meters wide. Uncle Doc said when he was a boy it wasn’t half that wide.

A spacious sand bar has formed on the far bank where the river bends around in a shallow dogleg. We had to walk through deep darkbrown sand strewn with carabao dung for over a hundred meters to get to the line of waiting trikes-for-hire. We passed a boy of about 7 or 8 placidly riding his huge lumbering carabao to give it a bath. I knew this since there was already three other carabao already enjoying their evening dip in the river. They are called WATER buffalo for a good reason.

We passed through tiny Callao where Atanacia said the Japanese had once burned alive about 80 villagers—men, women and children—an act of vengeance after Filipino guerrillas had attacked a Japanese patrol. She told us one more story about another nearby village where the people had had enough of the Nipponese slaughtering their carabao for a meal whenever they passed through. One day, as the Japanese soldiers sat down to another meal of “free” carabao steaks, the villagers made them “pay” the hard way, when they fell on the hapless imperial soldiers, slaughtering them to a man with their long bolo knives. Those deadly tools can make short work of a coconut, so a human skull would be no problem at all. Gomenasai!

Atanacia never stopped talking of her late husband, Adelberto. He died ten years ago, but to Atanacia he has never left her. Almost every other sentence starts with references to her beloved late spouse. We pulled up in front of her home in two trikes, just off a modest concrete road, and entered the low-walled compound. This was her family’s home ground; she had been born there in 1922, and I soon learned that she planned to be buried there as well.

Her house is a two-story cement block structure painted white and topped off with a blue-tiled roof. Much of the front is aproned with an expansive wraparound banistered patio, part of which is overhung by an equally expansive second floor terrace. It looked like a good place to sit outside and enjoy the morning and evening breezes, while shooting some with friends. Thirty-foot-tall Mango trees shade most of the property, and all the way to the back is a prominently white aboveground tomb. I asked her, “Is that where your husband is?” She proudly answered in the affirmative, remarking that they had built it a few years back and moved him in when flooding had compromised his original burial place. We walked back to inspect it. Two coffin-sized crypts stood side-by-side 8 feet high on the marble-encased platform. She pointed to one of the vaults stating that she would someday be laid to rest next to him.

The south side of the estate is devoted to growing crops and raising fowl and pigs. A humble wooden dwelling housed her fulltime caretaker. We took a seat in plastic chairs around a wooden table just outside of his hut, and Atanacia had him prepare three young coconuts. In no time there were four glasses of sweet coco water for us to enjoy. He offered the halved shells to us along with some spoons, and Doc and I dug into the soft white delectable inner coconut. The pigsties were just a few feet away, and unfortunately, the wafting smell slightly interfered with my coconut-enjoyment, but you get used to it after a few minutes I noticed.

The last of the ferries leave at 6 p.m., so we headed back to the waiting trikes. We made the long walk back through the sand, past fields of watermelon and tobacco. It was just past 6 and the only boat in sight was just pulling into the landing at the far side of the river. Oops. Uncle Doc waved his arms and whooped at the top of his lungs to get someone’s attention over there, but no one seemed to respond. We all sat down and waited as the evening grew darker and the air stiller. I didn’t have anything better to do that night, so I sat tight and enjoyed the calm beauty around me. After 45 minutes, a boat came across with a late load of passengers, and we had our ride home.

at 6 p.m., so we headed back to the waiting trikes. We made the long walk back through the sand, past fields of watermelon and tobacco. It was just past 6 and the only boat in sight was just pulling into the landing at the far side of the river. Oops. Uncle Doc waved his arms and whooped at the top of his lungs to get someone’s attention over there, but no one seemed to respond. We all sat down and waited as the evening grew darker and the air stiller. I didn’t have anything better to do that night, so I sat tight and enjoyed the calm beauty around me. After 45 minutes, a boat came across with a late load of passengers, and we had our ride home.

After seeing the last of our veteran clients late Thursday morning we had the rest of the day open, especially since there were no flights back to Manila until Friday. So we decided to hire Cherry’s van and do some sightseeing. That morning we headed north, up the Maharlika highway, towards Aparri to see “old and beautiful things,” as we instructed Cherry and Atanacia. We stopped at several interesting places: an Old Spanish Cathedral at Lalloc, the oldest church bell in the Philippines circa 1580, and finally the coastal city of Aparri. Our new family bought us lunch at a Japanese restaurant; we tried to pay, but again, they wouldn’t hear of it.

Before leaving Aparri, we drove down to the municipal beach. Doc struck off to the west and I headed east. I passed a large family on holiday, and they asked me to join them for lunch. I left my name and address when one of the ladies asked if I could help her dad with his benefits claim. Doc and I NEVER stop doing our job when it comes to helping our fellow veterans!

On the way back to Gatarran, we stopped at Cherry’s friend’s home to see her beautiful tropical garden featuring several types of orchids. I have similar flowers at my place, so what I found fun was exploring the back of their yard, which is dev

On the way back to Gatarran, we stopped at Cherry’s friend’s home to see her beautiful tropical garden featuring several types of orchids. I have similar flowers at my place, so what I found fun was exploring the back of their yard, which is dev oted to vegetables, carabao, pigs and chickens. One of our gracious hosts, an 18-year-old girl, led us all the way to the back of their place, where we scrambled down a small sandy hill to a creek featuring several carabao. I loved the bucolic setting, thinking, ‘Now THIS is TRULY the Philippines!’

oted to vegetables, carabao, pigs and chickens. One of our gracious hosts, an 18-year-old girl, led us all the way to the back of their place, where we scrambled down a small sandy hill to a creek featuring several carabao. I loved the bucolic setting, thinking, ‘Now THIS is TRULY the Philippines!’

By the time we got back to our lodge late that afternoon I was beat. My wooden box bed, with its two-inch foam pad, beckoned me. After  rinsing off the road grime with water ladled and splashed over my head from my all-purpose plastic bucket, I fell out for a much-needed nap!

rinsing off the road grime with water ladled and splashed over my head from my all-purpose plastic bucket, I fell out for a much-needed nap!

Friday morning the power went off while I was half way through my shaving routine. I finished packing, sans electricity, and headed over with Doc to the “Water Farm Diner” just up the road from us. If you ever drive through Gatarran and its time to eat, stop in there; it’s a good place to grab a sandwich or traditional Filipino fare. If you’re an American, you’ll feel right at home as it’s filled top-to-bottom with Americana. The owner, Norman, is a good guy. Doc and I enjoyed our conversations with him over our evening drinks. Almost every meal we ate was there at the Water Farm. Thank goodness it was there! We ate our breakfast and Cherry and her driver-husband came to pick us up just as we finished.

We left early so we would have time to stop at a place called Calvary in the town of Iguig before making our flight home. Once more, I enjoyed the Cagayan countryside, this time as we drove south back to Tuguegarao. Almost an hour into our ride, we entered the bustling town of Iguig. Cherry had to ask to make sure we turned up the proper road to the Calvary Cathedral, because the sign to the place, if there was one, was not well marked. We drove up a precipitous narrow drive and into a dusty parking lot in front of the ancient brick basilica. I was immediately captivated by the place.

The first thing that meets the eye is a huge statue of a

The first thing that meets the eye is a huge statue of a  “touchdown Jesus,” much like the large mural at Notre Dame University in Indiana. To the right of the parking lot is a grand old basilica built of fired red bricks. To the left is an ancient cement obelisk that is supposed to date back to 1765, or so says the placard.

“touchdown Jesus,” much like the large mural at Notre Dame University in Indiana. To the right of the parking lot is a grand old basilica built of fired red bricks. To the left is an ancient cement obelisk that is supposed to date back to 1765, or so says the placard.

Walking past the giant Jesus statue, I was drawn to a low stonewall overlooking a gorgeous vista of the Cagayan river valley. The view is stunningly beautiful. If we had had more time, I would have packed a lunch and soaked in the panorama while enjoying my meal. I’ve always loved being atop high places with special views, and that spot has both. By all means stop in and check it out; you’ll love it.

If you’re into architecture, the splendid old cathedral has a series of flying buttresses, also made of the old red bricks. They form a series of tall archways around the sides and back of the basilica. Without the buttresses the imposing sides of the church would have long ago collapsed under their own weight. I wish we had taken more time, so I could have explored the interior of that wonderful old structure. I love that stuff! Parts of the original edifice can still be seen where it was incorporated into the present building. It smells delightfully musty, like a delectably aged wine.

And finally, behind and past the church to the right, is a giant looping pathwa y that follows the rim of a large geological bowl. This natural amphitheatre must be at least 600 meters across and depresses into the ground 60 or 70 feet. I walked down a steep series of ancient concrete step-like seats behind the cathedral all the way to the bottom of the closely-cropped grassy bowl. (This stairway is described in the paragraph below). From that vantage, at the very center of the basin bottom, I could look up and see the gigantic series of statues depicting each of the 14 Stations of the Cross. Even if you are not Catholic, you will be impressed with the sublime loveliness of the place. Being there was truly inspiring, and I would love to go back and capture what I saw on film.

y that follows the rim of a large geological bowl. This natural amphitheatre must be at least 600 meters across and depresses into the ground 60 or 70 feet. I walked down a steep series of ancient concrete step-like seats behind the cathedral all the way to the bottom of the closely-cropped grassy bowl. (This stairway is described in the paragraph below). From that vantage, at the very center of the basin bottom, I could look up and see the gigantic series of statues depicting each of the 14 Stations of the Cross. Even if you are not Catholic, you will be impressed with the sublime loveliness of the place. Being there was truly inspiring, and I would love to go back and capture what I saw on film.

I found this blurb in a promotional “Come to Cagayan” site: “The Iguig centuries-old parish hill church is a popular tourist attraction. Iguig Calvary has The 14 Stations of the Cross depicted in larger-than-life-size concrete statues. The mildew-covered Rectory, constructed in 1768, was then the only source of drinking water. There is an ancient brick stairway to the west of the church, which was used by visiting Spanish dignitaries who traveled aboard barangays (bangka boats) that once plied up and down the river.”

So that’s it. It was a long post for such a short trip, but Cagayan is worth every second. I really want to go back. The sights are wonderful and the people are fantastic. Everyone I met had a greeting and a smile for me. If you want peaceful, friendly, and beautiful—Cagayan is the place!

Our van service driver, Roger Jr., as we call him, picked me up this morning at 6 a.m. for a trip to the Manila VA Regional Office. We got onto the North Luzon Expressway at the Angeles City – Magalang entrance and headed south toward Manila. I stared sleepily out the passenger side window watching as farmers winnowed their rice crop or burned the resultant waste straw. Why they burn it, I have no idea. They burn everything here; I hate that. I shrugged off that vexing question and settled in for the hour and a half ride to the U.S. Embassy.

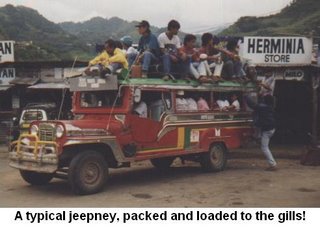

Our van service driver, Roger Jr., as we call him, picked me up this morning at 6 a.m. for a trip to the Manila VA Regional Office. We got onto the North Luzon Expressway at the Angeles City – Magalang entrance and headed south toward Manila. I stared sleepily out the passenger side window watching as farmers winnowed their rice crop or burned the resultant waste straw. Why they burn it, I have no idea. They burn everything here; I hate that. I shrugged off that vexing question and settled in for the hour and a half ride to the U.S. Embassy. back. I knew my hopes were in vain, because people tend to pack themselves by the bunch into cars and vans over here. It’s amazing how many they can fit in. Sometimes its like watching the little clown cars where one person after another climbs out, and 10 minutes later, they are still debarking. Folks around here are a lot smaller than Americans, so they can really pack ‘em in too!

back. I knew my hopes were in vain, because people tend to pack themselves by the bunch into cars and vans over here. It’s amazing how many they can fit in. Sometimes its like watching the little clown cars where one person after another climbs out, and 10 minutes later, they are still debarking. Folks around here are a lot smaller than Americans, so they can really pack ‘em in too! help.

help.

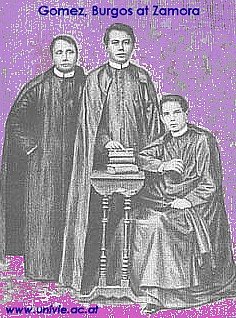

In fact, in 1872, Spain choked the lives out of three innocent Filipino priests in Luneta, which made them forever beloved and famous to generations of their countrymen. I’m an American, but I’ll never forget their names—Fathers Burgos, Gomez, and Zamora. Falsely accused of masterminding the '72 Cavite Rebellion, one of the priest

In fact, in 1872, Spain choked the lives out of three innocent Filipino priests in Luneta, which made them forever beloved and famous to generations of their countrymen. I’m an American, but I’ll never forget their names—Fathers Burgos, Gomez, and Zamora. Falsely accused of masterminding the '72 Cavite Rebellion, one of the priest

This two-lane cement road closely follows the eastern side of the Cagayan River. The ride north was pleasant with wonderful views of the wide river and its valley to the left, and vistas of gently rolling hills to the right. Both sides of our vehicle offered pastoral scenes of wallowing carabao, and well-tended fields of tobacco, corn, and rice. The steeper hills are heavily vegetated with bananas, mangos, palms and all sorts of other hardwood tropical trees. On the whole, I decided that its one of the most serene looking places I’ve yet seen in this country. The towns and villages pop up every ten or fifteen minutes of travel, and they are uniformly clean and well kept. I was impressed; Cagayan looks like a nice place to live.

This two-lane cement road closely follows the eastern side of the Cagayan River. The ride north was pleasant with wonderful views of the wide river and its valley to the left, and vistas of gently rolling hills to the right. Both sides of our vehicle offered pastoral scenes of wallowing carabao, and well-tended fields of tobacco, corn, and rice. The steeper hills are heavily vegetated with bananas, mangos, palms and all sorts of other hardwood tropical trees. On the whole, I decided that its one of the most serene looking places I’ve yet seen in this country. The towns and villages pop up every ten or fifteen minutes of travel, and they are uniformly clean and well kept. I was impressed; Cagayan looks like a nice place to live.

On the way back to Gatarran, we stopped at Cherry’s friend’s home to see her beautiful tropical garden featuring several types of orchids. I have similar flowers at my place, so what I found fun was exploring the back of their yard, which is dev

On the way back to Gatarran, we stopped at Cherry’s friend’s home to see her beautiful tropical garden featuring several types of orchids. I have similar flowers at my place, so what I found fun was exploring the back of their yard, which is dev